On September 10th, 2001 I had the last class of my Level 1 improv class at the UCB. We went out for drinks afterward and then back to a classmate’s apartment in the West Village to hang out some more. It was a good night. I remember leaving and putting a CD that I had bought from The Virgin Megastore into my Discman. I think it was an acid jazz collection.

I woke up the next morning and the world blew up.

I saw the smoke in the sky that morning when I stepped out of my apartment to walk to the L train to go to work. Or maybe I saw it from my bedroom window. I could see the towers from both my bedroom and bathroom windows in Williamsburg. I remember thinking that smoke in the sky wasn’t that odd or cause for alarm. Looking back I also realize that I had no concept of the scale of the World Trade Center because when someone on the street told me, “a plane crashed into it,” I thought it must have been a small two seater plane or something, a bad accident, sure but nothing terrible. It didn’t occur to me that the World Trade Center was as wide, or actually wider, than the wingspan of a Boeing 767.

People in my neighborhood weren’t screaming. No one was panicking. We were still in the last few minutes of a normal world. So, I got on the subway and went to work. That is so absurd to me in retrospect. I just want to take a moment and give myself a slow clap. After the first plane hit the first tower, that is to say after phase one of the most devastating terrorist attack in the history of the United States, I thought, “huh, oh well. Gotta get to work!”

The other plane hit while I was underground. The mood when I got to street level was different. Now, people were panicking. No one knew what was going on but, while I was underground, people on the street had witnessed the second plane flying into the building. I got to my office on 38th street between 5th and Madison and when I got to my floor, the radio was on and my co-workers were listening to what was happening.

I heard the towers collapse over the radio. The newscaster screamed as the first tower came down. My co-workers gasped. I felt numb. Then the second tower fell. I’m glad that when it happened I only heard it. We would all see it again and again and again in the days to come but I was so grateful I didn’t see it live. The audio was enough.

I needed to call my mom just to let her know that I was fine. I had just gotten my first cell phone. I held out for a few years but finally caved. I tried to call her but all so many calls were going through that it was hard to connect. I finally got her and she was so relieved which surprised me because she knew I worked miles away from there.

When it was safe to leave, we were all dismissed from work. We knew that the subway was shut down. I don’t remember if they had put up the barrier at fourteenth street yet. Later, on the news, I would see thousands upon thousands of people walking home over the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg Bridges. I didn’t want to walk back to Brooklyn. My roommate Jon was out of town and I needed to be around people. I went home with my co-worker Jon, who lived on the Upper East Side.

We walked from 38th Street to the East 90’s and it was one of the most bizarre experiences of my life. Do you remember how beautiful it was that day? There’s a certain type of fall day that only happens in September, where it’s warm but crisp and the sky is bright blue. September 11th was one of those days and on this particular day, the streets of New York were packed with New Yorkers walking home but they were all so quiet. It was as if we were all in a library. I doubt I will ever see that again, that many New Yorkers on the street during a beautiful day, calmly and silently walking home. My roommate Jon had just given me the book White Noise to read and the whole experience reminded me of the Airborne Toxic Event, where people flee a black cloud of toxic smoke. We were all slowly and quietly fleeing the toxic cloud left by the towers. We were all going home to what? To await instructions? Find out what the hell happened?

He had two or three other roommates and we all gathered around the television to watch the news coverage and watch the planes crash into the towers over and over and over again. They showed the image of smoke emanating from the place where the towers used to be.

The next day on a similarly beautiful September 12th we all went to a surprisingly packed Central Park for what Jon jokingly called National Pretend Everything’s Okay Day. We were on the Great Lawn over a hundred blocks away and I could smell the smoke from the towers.

A few days later I went back to my apartment. The woman on the second floor told me that my landlady’s mother, who lived on the first floor, had gone to my apartment door to knock a few times, coming away crying each time. So, I knocked on her door and gave her a hug and let her know that I and my roommate were fine. She didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Spanish but somehow we were able to communicate to each other that I was fine and she was glad I was alive.

A high school classmate was in one of the towers. I went to Camp Stella Maris with him the summer between seventh and eighth grade. We weren’t close but I knew him. A few weeks later, I got a beer with a college friend and a friend of his who lost most of his the people in his office. He just happened to be late to work that day. I heard stories of people waking roommates to get to work on time, successfully though unintentionally sealing their friend’s fate in the towers. I heard another story about a guy unable to find his wife, a flight attendant in the DC area. They ultimately found her in a hotel room with another man, a pilot. It was a surreal day.

As days and weeks passed, I remember thinking that things were going to be okay. We mourned and paid tribute to all the victims and firefighters. It would take a while but things would be okay. We all started going back to work. Jon Stewart cried on The Daily Show. The Onion put out a classic post 9/11 issue. Mike Piazza hit a homerun. SNL came back on the air. It felt like everyone was getting along.

It felt uneasy, though. Much like the Great Lawn on “National Pretend Everything’s Okay Day” there was so much beneath the surface. It seemed like we were all trying to pretend that things were getting back to normal.

A month later, in October, I was with my girlfriend at the time and her family. We were picking apples in New Jersey. My girlfriend’s cousin heard from a friend that we had just started bombing Afghanistan.

On the way home from New Jersey, on the PATH train, underground, something popped and the lights went out and the train came to a stop I thought that I was in another attack. It turned out to be some minor track problem but that day was when the fear really started.

We were at war. The Gulf War scared me when I was a kid but I felt protected because I was too young to fight and because it was so far away in the Middle East, this place that I knew nothing about.

I knew maybe two or three Muslims in my life before then but now Islam was a topic of discussion everywhere. Well over a billion of them on earth and I knew two or three in my lifetime.

I wouldn’t fly in a plane for years. Terrorism and the threat of it became a permanent part of our lives. Dirty bombs and attacks in the subway were always on my mind. I would take the JMZ over the Williamsburg Bridge to get home because if there was an attack, I wanted to be out in the open rather than under the East River on the L train. I would return home and feel safe for some reason, safe that I was away from any possible bombs in public transportation or a suicide bomber or a building exploding, anything. I was like a child hiding under his blanket from a monster.

I talked to my parents about leaving New York and they both told me no. My mother’s relief on 9/11 had quickly done a 180. I was so scared of an attack but she said, “you know what, Rob? If you get killed, you’re dead. You won’t feel it.” It was pretty frank and I wonder if she meant that or if she was scared for me but knew that I belonged in New York. My father, having lived through bombings in England as a child during World War II was infuriatingly unfazed by the whole thing.

That period of fear seemed interminable. Terror alerts and jihad and weapons of Mass Destruction and Bush and Cheney and Osama and Saddam and smoke ’em out and you’re either with us or against us and the hijackers and seventy-two virgins and The Taliban and anthrax. All I could really think is, how will we ever get over this?

On the first anniversary, I was terrified because people were saying that the terrorists were going to try to repeat the attacks as a tribute and, at that time, I still listened to people who said things like that. On the second anniversary I was still afraid. On the third, I was less so and then with each subsequent year I just said to myself, “wow, can you believe it’s been X years?”

In the years since I watched both of my parents take their last breaths in hospital beds but I still consider 9/11 to be the worst day of my life.

Now there are memorials where the towers used to be. There is a new building. There’s a museum. They sold a cheese plate in the museum gift shop. Maybe things aren’t normal but they feel about as normal as they can be, for us in America, anyway.

Chris Rock made a joke in his SNL monologue a couple of years ago. “They should change the name from the Freedom Tower to the Never Going in There Tower. Cause I’m never going in there.” I had the same thought but this past week I went to One World Trade and I went to the top. I felt a pang of fear as I went into the building and took the elevator to the observation deck but it faded fast. It was an overcast day and I was a little underwhelmed by the site because for every interesting building or neighborhood I could see, I knew that I had walked there at some point in my seventeen years in this city.

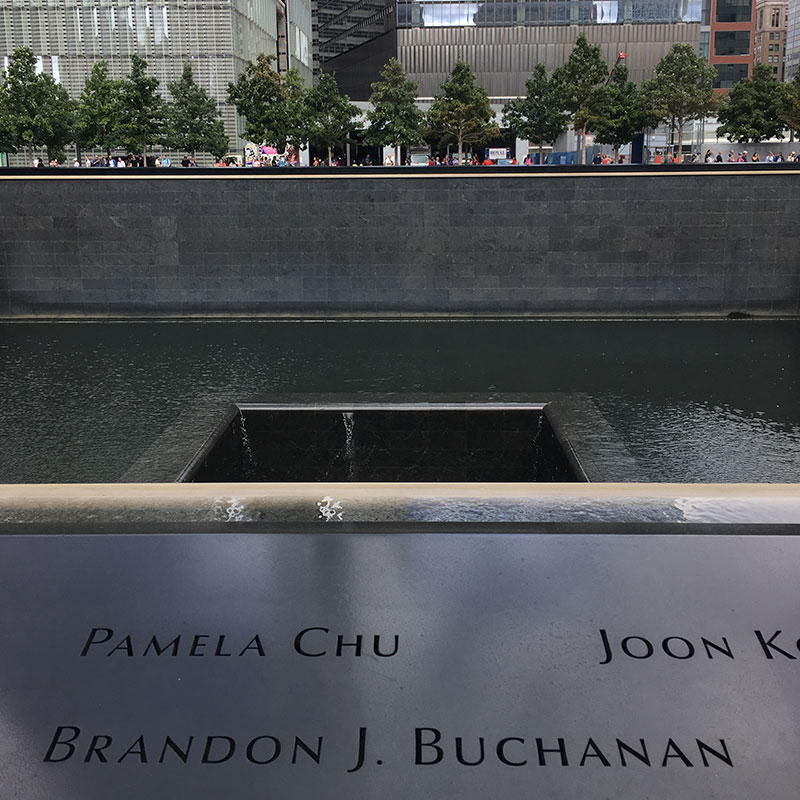

I went back down and walked around the memorial until I found my friend’s name.

Here’s the part where I say to myself, “wow, can you believe it’s been 15 years?” Yeah. I can. I always thought, how are we going to get through this? We’ve been getting through it the way you, ultimately, get through anything. You let time pass.