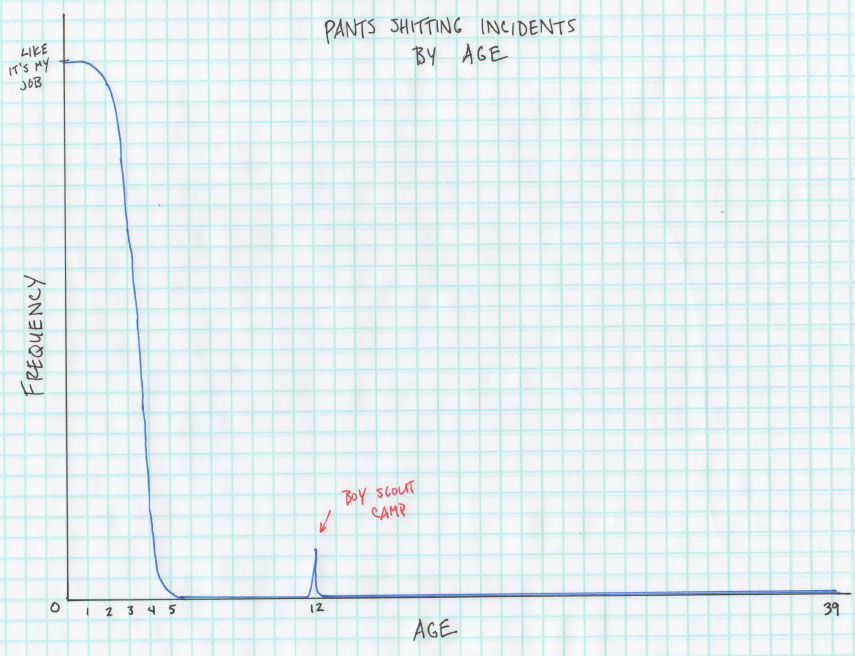

In my first storytelling class my teacher Adam Wade told us that everyone has a shit story and, in the years since, I’ve seen that this is true. I used to think mine was special but everyone thinks that at first. A week ago I heard a storyteller tell his with the self deprecation and humiliation of someone revealing it for the first time. Yeah, we all have one.

I would imagine that most of us, if we were to look at the data, would have find a graph similar to my own (Fig. A) below. The goal, as an adult, is to keep pants-shitting to a minimum, ideally zero incidents. But we all have a blip in our graph, i.e. our shit story.

If we all have a shit story, I’m just going to go out on a limb and assume that we all have several near misses as well. Those of us who live in New York certainly must experience this, often hearing nature call when we are as far from nature as humanly possible. In my own experience, as I am the hero of my extremely low stakes life, the need to use the bathroom becomes a Jason Bourne-esque action sequence complete with shaky Paul Greengrass cinematography, rushing through New York crowds, constantly eyeing the area around me for a safe space or a way out.

I experienced this recently. I was in the subway waiting for the Brooklyn bound R at Whitehall Street to go home after an interview when I realized that I had to go. Now, spoiler alert, I made it. I’ve kept my clean sheet for my twenties and thirties but what interested me, in the calm after the storm, was the amount of instantaneous calculation that my mind performed to get me out of this jam.

So, what follows is my analysis of how I came to poop in the Staten Island Ferry Terminal bathroom.

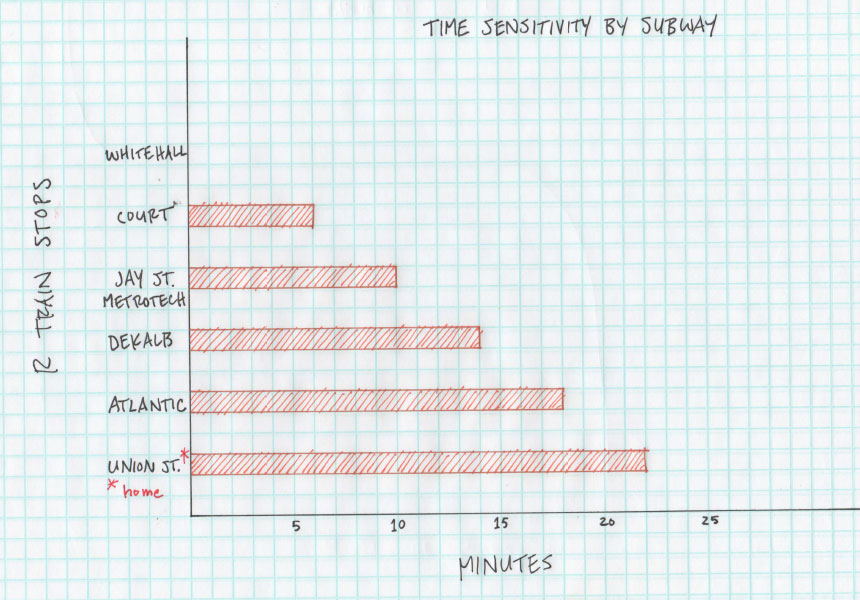

My first unconscious calculation was simply one of time (Fig. B). How long will it take me to get to my first choice bathroom spot, i.e. home? I estimated the amount of time with each subway stop acting as a possibly escape hatch should the occasion call for it. I estimated six minutes to Court Street then four minutes for every subsequent stop, putting me at home in approximately twenty-two minutes.

Not impossible, so I took a cleansing breath.

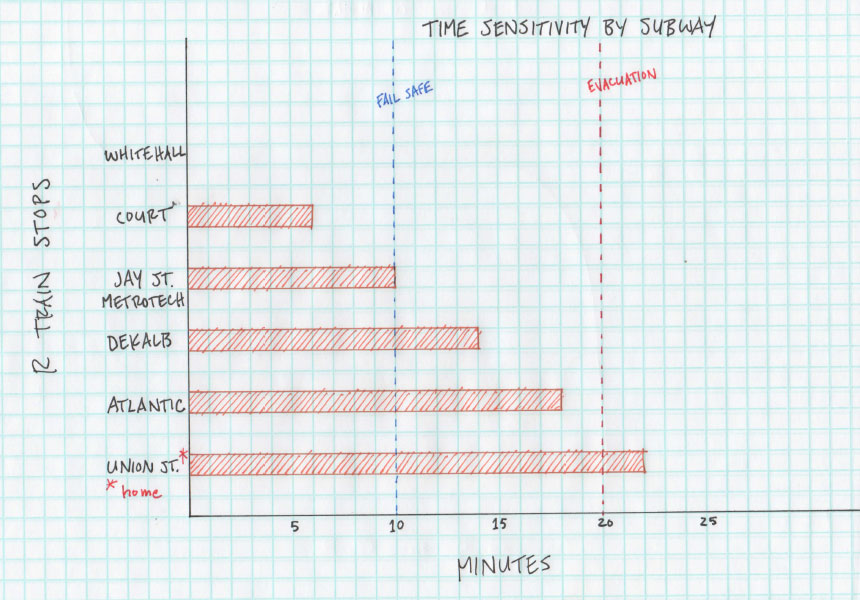

Now there have been times when I’ve kept the urge at bay for upwards of an hour. Other times I’ve felt the urge disappear completely. I don’t know which neurons fired that conveyed the gravity of the situation but my body let me know that, on this day, neither of those outcomes would be the case.

I had to recalculate.

I gave myself a ten minute window before the fail safe, the point of no return, the point beyond which there could exist no activity other than finding a bathroom. Having constructed a more realistic timeframe (Fig. C), I came to the stark realization that I wasn’t going to make it home.

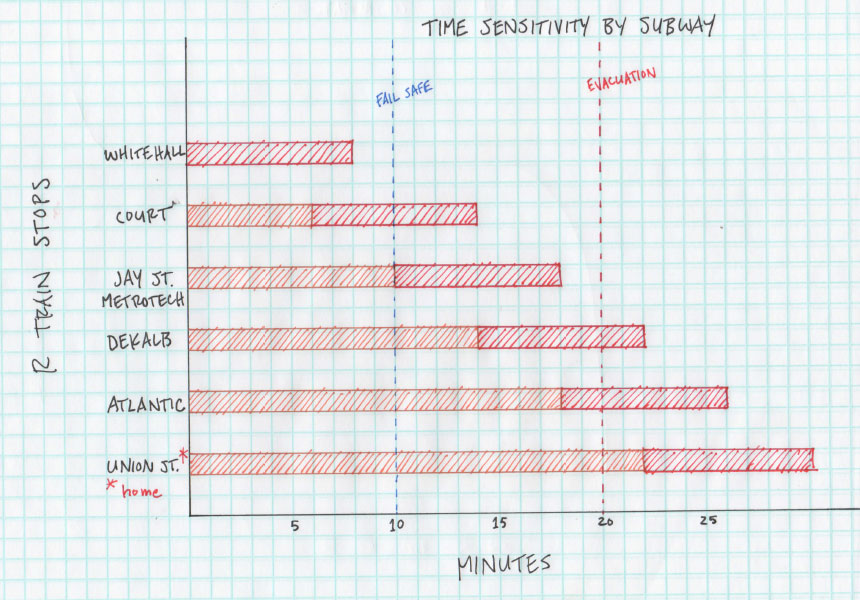

This realization prompted me to consider even more practical concerns. You have to take into account the time it takes to exit the subway station (have you ever tried to exit the Court Street R? There’s a goddamn elevator). Then you have to take into account the amount of time it takes to search for an acceptable bathroom ideally of the Barnes and Noble, upper tier chain restaurant, or Starbucks variety. But even taking that into account you have to budget for a possible line, frantic seat cleaning, and, God forbid, a bathroom code. (I’ve always wondered, if it really came down to it with a strict manager who insists, “you’ve got to buy something” would I have the balls to get all Jack Bauer on him? “There’s no time! GIVE ME THE BATHROOM CODE!”)

For this new set of obstacles, I mentally added eight minutes to the process, changing the picture completely. As you can see from Fig. D, this leaves me with the possibility either Court or Jay Street Metrotech with possible bowel release right before pulling into Dekalb, probably beneath Juniors on Flatbush Ave.

Taking all of this into account, I knew that the most prudent course of action would be an immediate subway exit to begin my search.

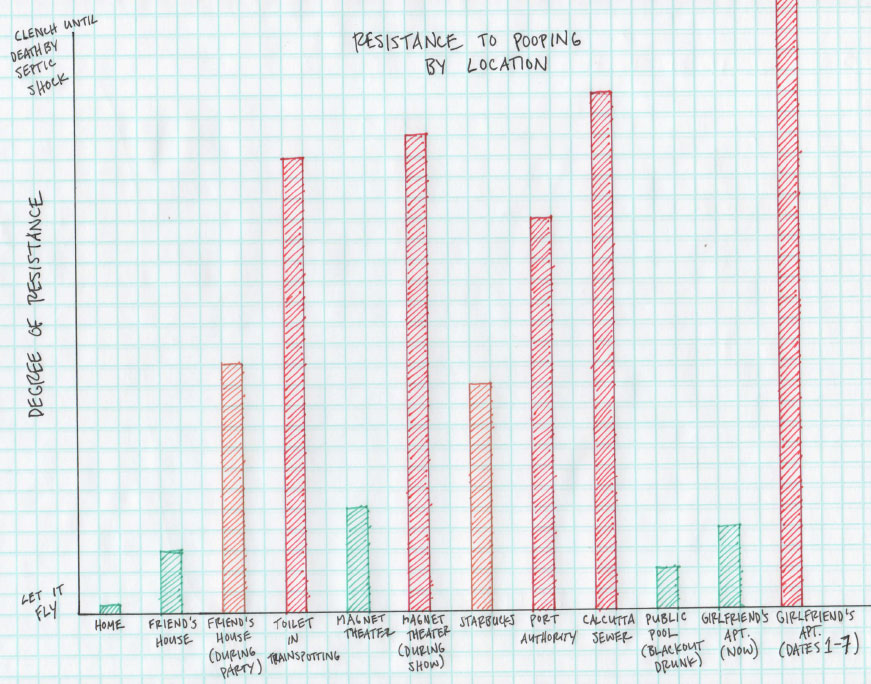

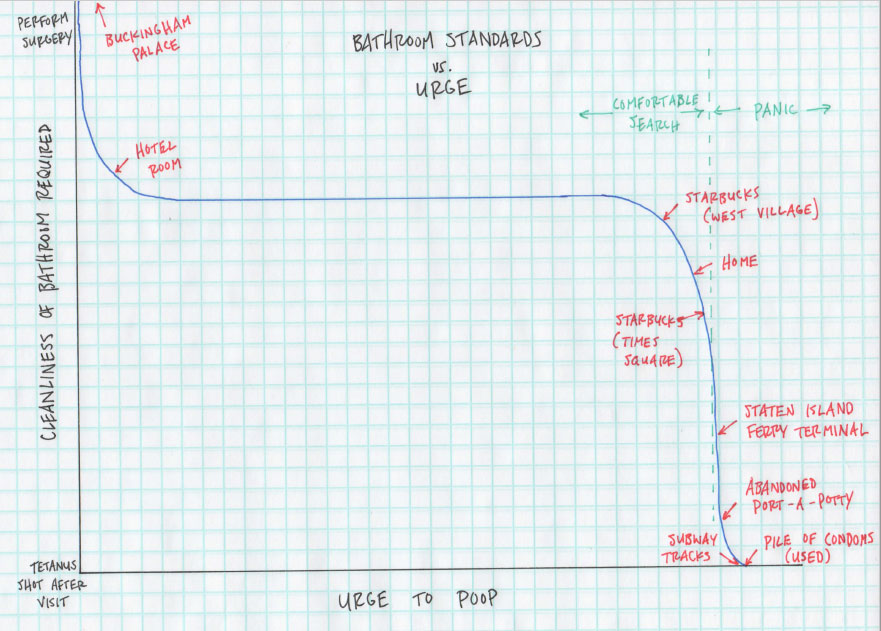

I was unfamiliar with the area outside the Whitehall station but I knew that the aim was to locate a first tier bathroom, like the previously mentioned Starbucks. Location matters and as I hit the street, refusal by location was still an option. A glance at Fig. E will show you my relative preferences.

The preceding bar graph, however, was made including the luxury of time. If you draw your attention to Fig. F you will see that standards drop precipitously as the urge grows.

There were no Starbucks that I could find, no welcoming clean, empty chain restaurants who wouldn’t mind a non-paying, sprinting customer making a quick visit.

So I had to go public. The nearest public anything was, in fact, the Staten Island Ferry Terminal. As you can see below from Fig. F, I actually timed it quite well, just after panic but before any truly regrettable actions needed to be taken.

My calculations were pretty much correct regarding New York City public bathrooms (assuming all rate around the same as Port Authority in Fig. E). When you fear for the cleanliness of your pants and belt buckle that may or may not have touched the ground, you know you’re in a public New York City bathroom. But I maintained my blip-free thirties (Fig. A) and that was all that mattered.

A solitary figure walked back to the R train. Back home. “Extreme Ways” played as the credits rolled.