I remember having a conversation with my friend Nick where we agreed that if we had to describe what music sounds like now, we wouldn’t be able to do it. We had that conversation around 2013 or 2014.

Classic rock stays the same. Radio stations have been playing those songs over and over again for thirty or forty years. Elvis and Bill Haley and the Comets sound like the fifties. The Doors and The Beatles and The Byrds sound like the sixties. Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath sound like the seventies. The eighties sounds like hair metal and Whitney Houston. The nineties sound like grunge and new jack swing.

I didn’t think that what I thought of as now, which was really a time period that stretched well over a decade from 2000 on, had any distinctive sound.

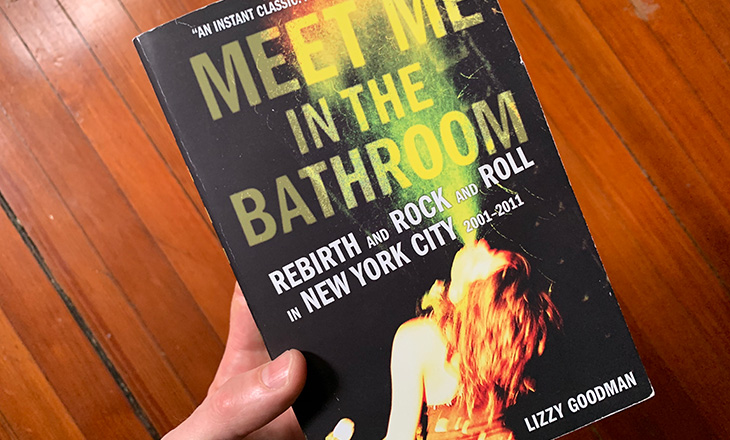

I didn’t realize that I was wrong until I read Meet Me In The Bathroom by Lizzy Goodman. The oughts, especially the early oughts, has a distinct sound and it came, for the first time in a long time, from New York.

Meet Me in the Bathroom completes the trifecta of brilliant music books along with Our Band Could Be Your Life and Please Kill Me. Meet Me in the Bathroom is more resonant for me because I lived through it, however tangentially.

I had been in New York for a little over a year when my friend Jon (co-worker Jon, not oldest friend Jon) told me about this great band that he had just seen called The Strokes. He had seen them in some small dingy club downtown. A week later – or so it seemed – they were everywhere. That yellow fractal looking album cover for Is This It was everywhere. Skinny jeans and Converse sneakers were everywhere.

Bands named The Somethings exploded. The White Stripes, The Hives, The Vines, The Killers, The Moldy Peaches. I wasn’t cool so I got all of my music from the Virgin Megastore in Union Square (sometimes from the one in Times Square). That’s where I got the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Fever To Tell and Interpol’s debut album. My friend Pat told me about Bloc Party and gave me a Doves CD for my birthday.

I didn’t realize that The Strokes and Interpol had sort of a Beatles / Stones thing (respectively). I can understand that and even though The Strokes are more of an era defining band and even though there are entire episodes of my life for which Is This It is the soundtrack, I’ve always been an Interpol guy. (And for Christ’s sake, I don’t think they sound a thing like Joy Division. That’s my belief, I’m sticking to it.)

I’ve long had a gripe with the rather pervasive opinion that New York has lost its soul. For one, if you don’t like it, leave. Secondly, I’m always annoyed that anyone who complains about what New York has become is just pining for the seventies. Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, I bought smack everywhere, I got mugged fourteen times, now I can’t afford to be an artist, blah blah blah.

If there’s one refreshing thing about Meet Me in the Bathroom, it’s that all of the people are referring to a magic time in New York but their magic time was the nineties. Who knew? I thought everything about New York became lame the second Reagan was elected but I guess I was wrong. I’ve been here for 20 years and New York had already lost its soul by then: Giuliani, the dot com boom, the Disneyfication of Times Square, et cetera.

The book starts off talking about a band called Jonathan Fire*Eater – the spiritual forefathers of the early oughts New York bands – and the Lower East Side of the nineties. Max Fish and Luna Lounge and 2A. Then it veers into Brooklyn, at a time when Williamsburg was still cheap and full of lofts.

This is the weird part because I was there. Sort of. I wasn’t part of any of that scene. I didn’t see a lot of live music and apparently not doing cocaine precludes one from a lot of the experiences and locales talked about in this book.

It still made me nostalgic, though. The book reminds me of a time that wasn’t that long ago but is still quite different. Media changed. Blogs and music sharing services like Napster changed everything. Tunde Adebimpe from TV on the Radio was asked to sign a ripped copy of his own CD before it had been released. And now even that kind of experience is a thing of the past. It’s just all on Spotify.

My friend Pat and I hung out at 2A all the time because our friend Jeff’s sister bartended there. Apparently The Strokes hung out there. I never saw any of them but that’s where Julian Casablancas met his wife.

I moved to Williamsburg but I didn’t live in a loft or at the Bedford stop – and in 2000, in my world, that was all that counted as Williamsburg. The Lorimer stop, where I lived, was out in the wilderness of Brooklyn. I used to walk to the Bedford area to get coffee and a bagel (in what is now a candle shop and an Apple Store, respectively) and saw Kyp Malone, guitarist for TV on the Radio, quite a bit.

Like I said, I was there. Sort of.

At the time, I was more interested in comedy. I would arrive hours early to 22nd street on a Sunday to get in line to get free tickets to the 9:00PM ASSSSCAT at the UCB and watch Amy Poehler and Tina Fay and one time – one time only but I’ll remember it until the day I die – Will Ferrell. I was in improv classes and telling bad jokes into microphones in basements. It was wonderful.

This brings me to a gripe I had with the book. All of these people, all of these musicians, kept referring to themselves as outcasts. These rock stars and journalists who all hung out together, did drugs together, partied together, slept together, and defined a generation together kept calling themselves outcasts.

Take it from an actual outcast, if they let you in the party and then they give you cocaine and have sex with you, you aren’t an outcast. You are very very cool. A true outcast would be home on a Saturday night at his apartment on 82nd and York renting Never Been Kissed from the Champagne Video on the corner. (And if you are currently asking yourself, “Wait, did you really do that?” we haven’t met.)

I guess everyone sees themselves as the maverick hero of their own story. It just bugged me a bit.

There were other parts of the book that I had no idea about.* I knew nothing about Fischerspooner or electrocrash (the first time I heard the term, it was used derisively because it was already over) or the drama behind James Murphy and LCD Soundsystem. It reminded me of bands like The Kings of Leon and provided several firsthand accounts of Ryan Adams being a dick. Karen O is cooler than I’ll ever be. White Blood Cells is a fantastic album – go listen to it now.

* I have one petty problem with the book and that is the inclusion of Vampire Weekend. I’ve tried to listen to them but I just can’t stand them. They’re quirkier than Zooey Deschanel crocheting a ukulele for her french bulldog that rides a unicycle. They make the Moldy Peaches sound like AC/DC. Having a song called “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa” should have gotten them thrown down a flight of stairs leading to a group of skinheads wearing steel-toed boots ready to kick their Ivy League teeth in. They sound like a Paul Simon cover band playing a talent show in a dorm at Exeter. Their albums could make Wes Anderson scream, “Jesus Christ, grow a pair!” They’re the auditory equivalent of ordering a set of spare croquet mallets from LL Bean. And yeah they have many influences and they’re a product of a new generation of millenial musician unencumbered by having to identify with one brand of music and opened themselves up to many influences and blah fucking blah fucking blah. That doesn’t change the fact that they sound like George Plimpton freebasing William F. Buckley.

True to form for a rock book many of those interviewed ended up either sober or dead. It’s funny that I had to read a book to remind myself of a decade of my own life. Whether you were there or not, you should read this book.

But seriously, though, if i had to describe the sound of music now, like now now, I don’t think it sounds like anything, not like music from the oughts did anyway. That was some good music.